“Las herramientas digitales están cambiando casi a diario, profesores y estudiantes están aprendiendo estas nuevas tecnologías juntas, que proporciona un práctico, experiencia de aprendizaje colaborativo.” – Cleary Vaughan-Lee

Stories bring us together, y desde 2006, El Proyecto de Unidad Global ha centrado en la narración sobre las culturas mundiales como una herramienta para ayudar a los estudiantes entender su mundo mejor. El proyecto produce películas documentales que se cuentan a través de las voces de las personas y comunidades. Se pone “un rostro humano a los problemas globales,”Explica el director ejecutivo de Cleary Vaughan-Lee. Each story must reflect “universal values, such as resilience, diversidad, responsabilidad, and love.” Films transport us. Students can meet “an indigenous fisherman in Alaska experiencing the decline of his subsistence lifestyle, a young Syrian refugee who fled imprisonment and war to seek political asylum in Canada, or a community living in Flint, Michigan suffering from the impacts of the water crisis.” Learning about these cross-cultural experiences teach students to “question the world” while “reflecting on their own perspectives and lives.”

Cleary Vaughan-Lee founded the education arm of the Global Oneness Project in 2010, where she is the Education Director. La Búsqueda Global para la Educación is pleased to welcome Cleary Vaughan-Lee to talk about the growth of immersive storytelling as a global learning tool.

“A mi, being a global citizen is to think about being a member of the world. To be a global citizen is to care about the people and land that is our home.” – Cleary Vaughan-Lee

Cleary, how has e-learning evolved since you started in 2005? What differences have you seen in the way classrooms use it today to enhance learning versus when you started out?

E-learning and the media landscape has changed and evolved rapidly over the last decade.

Since the mid-2000’s, with the creation of YouTube and the first iPhone, many students now have increased access to global learning from online and digital resources and can be exposed to the world so much faster.

In the last decade, we’ve seen e-learning expand with blended learning, flipped classroom models, media creation tools, and open educational resources (OER). We’ve specifically seen a shift with video content being used five or six years ago as a source of entertainment to now being integrated into a classroom’s curriculum. Multimedia can help to strengthen 21st-century learning skills, including media and information literacy, while addressing instructional goals.

Rather than being seen as an external source, multimedia storytelling is now being used as multimodal sources to strengthen literacy skills and address cultural awareness.

Digital content providers and e-learning platforms have expanded exponentially in the last decade. Platforms like Khan Academy, Comparte mi lección, PBS Medios de Aprendizaje, National Geographic, La red de aprendizaje del New York Times, Edmodo, and TED-Ed offer a variety of rich content that is accessible for any grade level or subject. Google tools—including Classroom, Slides, and Docs—have also grown to support teachers in creating assignments as well as ways to communicate with students.

Las herramientas digitales están cambiando casi a diario, profesores y estudiantes están aprendiendo estas nuevas tecnologías juntas, que proporciona un práctico, collaborative learning experience.

What does it mean to be a global citizen?

This is a question I consider frequently. A mi, being a global citizen is to think about being a member of the world. To be a global citizen is to care about the people and land that is our home. The Asia Society defines global competence by actively engaging students with the following core components: investigating the world, weighing perspectives, communicating ideas, and taking action. We incorporate these components into our lesson plans.

Our stories and lessons are being used in grades 5 -12 in multiple subject areas in the arts, ciencias, and social sciences. Students are exposed to the world’s cultures, which bring the world to the classroom to students who have not yet traveled outside of their local environments. Some of the global issues explored in our stories and lessons include the following: cambio climático, cultural displacement, corporate abuses, cultural preservation, food insecurity, globalización, derechos humanos, inmigración, language loss, migración, modernization, pobreza, and sustainability. Through the stories, students can connect to a world much bigger than the one they know, ask global to local questions, and think of potential solutions.

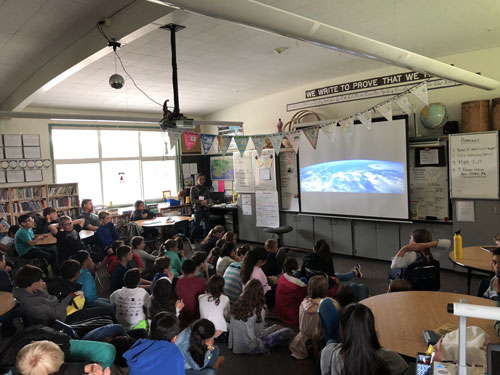

How can we prepare students to become perceptive and engaging global citizens? One of my favorite films, which gets to the heart of global citizenship, es Earthrise. The film tells the story of the Earthrise photograph, taken in 1968 on the Apollo 8 misión. Told solely by the Apollo 8 astronauts, the film captures the beauty, awe, and grandeur of the Earth against the blackness of space. This was the first time in history that humanity witnessed the Earth as one ecosystem and one shared home.

I particularly enjoy this passage from the director of Earthrise, Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee. He wrote, “I wanted to create that human connection to the Earth…I wanted to explore how to feel and witness the Earth as our home the way the Apollo 8 astronauts had. I wanted to share the awe and beauty they had experienced, to remember the power of this image they shared with the world.”

Our Project aims to make connections that highlight humanity’s interconnectedness on multiple levels to allow students to develop empathy and care for our world. Getting to the heart of global learning is making global issues relevant and accessible for students to evolve as self-confident global citizens.

“Many teachers are creating PBL projects using our stories as a foundation.” – Cleary Vaughan-Lee

A teacher wants to implement the Global Oneness Project program in his/her curriculum. How does she/he get started?

Primera, I would recommend viewing this short video clip, which provides an overview of the Project. Entonces, to get an overview of the stories we tell, watch this 3-minute film reel.

Our website contains over 50 short documentary films, ranging in length from 3-25 minutos, and over 40 photo essays, which geographically span the globe and represent communities on every continent. All of resources are free; you do need internet access. You might be a social science educator looking for a story from a particular region in the world or an English language arts teacher looking for ways to bring in a specific theme that connects to the curriculum’s reading assignments. School districts have also added our resources into their curriculum maps.

To start, I always recommend choosing a story that inspires the educator. All of our stories highlight elements of culture including family, religion and beliefs, idioma, societal rules, ciencias económicas, literatura, and traditions. Mayoría de las veces, in our professional development workshops, educators share their own cultural heritage stories after watching a film. These stories make their way back to the classroom, providing meaningful connections. One story many educators begin with is Diccionario de Marie.

La cantidad de elección de los estudiantes y de la voz del estudiante es parte integral del programa de aulas?

The stories on our website are curated into various collections, including ones on migration, cambio climático, endangered cultures, nature, inspiring people, y la creatividad. We frequently create additional collections on specific themes, such as ones on youth perspectives, empatía, breaking down stereotypes, family traditions, and identity and place. These collections are used by educators, specific to their subject focus and instructional goals, and provide ways for students to select a story of their choice.

Many teachers are creating PBL projects using our stories as a foundation. Students choose a story, surrounding a particular theme or global issues, conduct research, ask questions, respond to writing prompts, and present their findings in their classroom or during school-wide events. Projects take the shape of public service announcements, short films, poesía, fotografía, and letters to the filmmakers or to community leaders. Our films are also used in classrooms or during school-wide film festivals or screenings. Students then host panel discussions with their communities to think deeper about global issues and offer potential solutions.

“How can students contribute to creating a better world? There is an urgency to address this question.” – Cleary Vaughan-Lee

¿Cuáles son los mayores desafíos que ha enfrentado?

One of the biggest challenges we face is staying up to date with emerging technologies. The technology of virtual reality, por ejemplo, is not yet accessible to the mainstream. What role will these technologies have on the future of education?

What can we expect from the Global Oneness Project in the next 10 años? ¿Cuáles son sus objetivos principales?

We’ll need stories that highlight our common humanity as much as we need them now. How can we challenge students to create more solutions-based thinking towards some of our most pressing global issues? We will ask ourselves this question as we move forward.

We will continue to offer educators and students free tools and resources to explore universal values through immersive storytelling. It is our hope that these stories will inspire teachers to approach learning from a personal perspective and encourage students to make informed decisions, persist through challenges, become effective problem solvers as well as cultural and environmental stewards. How can students contribute to creating a better world? There is an urgency to address this question.

C. M. Rubin and Cleary Vaughan-Lee

Gracias a nuestra 800 más contribuyentes globales, profesores, empresarios, investigadores, líderes empresariales, estudiantes y líderes de opinión de cada dominio para compartir sus puntos de vista sobre el futuro del aprendizaje con La Búsqueda Global para la Educación cada mes.

C. M. Rubin (Cathy) es el fundador de CMRubinWorld, una compañía de publicación en línea se centró en el futuro del aprendizaje global y el co-fundador de Planet Aula. Es autora de tres libros más vendidos y dos series en línea leído. Rubin recibió 3 Premios Upton Sinclair para “La Búsqueda Global para la Educación”. La serie que aboga para todos los estudiantes se lanzó en 2010 y reúne a distinguidos líderes de opinión de todo el mundo para explorar las cuestiones clave de la educación que enfrentan las naciones.

Siga C. M. Rubin en Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

La Búsqueda Global para la Educación Comunitaria Página

Comentarios recientes