“デジタルツールはほぼ毎日変化しています, 教師と生徒は一緒にこれらの新しいテクノロジーを学んでいます, 実践的な, 共同学習経験。” – クリアリーヴォーンリー

物語は、私たちを一緒に持って来ます, それ以来 2006, グローバルワンネスプロジェクトは、学生がより自分の世界を理解するのに役立つツールとして、世界的な文化についての物語に焦点を当てています. プロジェクトは、個人やコミュニティの声を通して語られドキュメンタリー映画を生成します. これは、地球規模の課題に」人間の顔を置きます,」エグゼクティブディレクタークリアリー・ヴォーン・リーは説明します. Each story must reflect “universal values, such as resilience, 多様性, 責任, and love.” Films transport us. Students can meet “an indigenous fisherman in Alaska experiencing the decline of his subsistence lifestyle, a young Syrian refugee who fled imprisonment and war to seek political asylum in Canada, or a community living in Flint, Michigan suffering from the impacts of the water crisis.” Learning about these cross-cultural experiences teach students to “question the world” while “reflecting on their own perspectives and lives.”

Cleary Vaughan-Lee founded the education arm of the Global Oneness Project in 2010, where she is the Education Director. 教育のためのグローバル検索 is pleased to welcome Cleary Vaughan-Lee to talk about the growth of immersive storytelling as a global learning tool.

“私には, being a global citizen is to think about being a member of the world. To be a global citizen is to care about the people and land that is our home.” – クリアリーヴォーンリー

Cleary, how has e-learning evolved since you started in 2005? What differences have you seen in the way classrooms use it today to enhance learning versus when you started out?

E-learning and the media landscape has changed and evolved rapidly over the last decade.

Since the mid-2000’s, with the creation of YouTube and the first iPhone, many students now have increased access to global learning from online and digital resources and can be exposed to the world so much faster.

10年で, we’ve seen e-learning expand with blended learning, flipped classroom models, media creation tools, and open educational resources (OER). We’ve specifically seen a shift with video content being used five or six years ago as a source of entertainment to now being integrated into a classroom’s curriculum. Multimedia can help to strengthen 21st-century learning skills, including media and information literacy, while addressing instructional goals.

Rather than being seen as an external source, multimedia storytelling is now being used as multimodal sources to strengthen literacy skills and address cultural awareness.

Digital content providers and e-learning platforms have expanded exponentially in the last decade. Platforms like Khan Academy, 私のレッスンを共有します, PBSラーニングメディア, ナショナル・ジオグラフィック, ニューヨーク・タイムズ学習ネットワーク, Edmodo, and TED-Ed offer a variety of rich content that is accessible for any grade level or subject. Google tools—including Classroom, Slides, and Docs—have also grown to support teachers in creating assignments as well as ways to communicate with students.

デジタルツールはほぼ毎日変化しています, 教師と生徒は一緒にこれらの新しいテクノロジーを学んでいます, 実践的な, collaborative learning experience.

What does it mean to be a global citizen?

This is a question I consider frequently. 私には, being a global citizen is to think about being a member of the world. To be a global citizen is to care about the people and land that is our home. The Asia Society defines global competence by actively engaging students with the following core components: investigating the world, weighing perspectives, communicating ideas, and taking action. We incorporate these components into our lesson plans.

Our stories and lessons are being used in grades 5 -12 in multiple subject areas in the arts, サイエンス, and social sciences. Students are exposed to the world’s cultures, which bring the world to the classroom to students who have not yet traveled outside of their local environments. Some of the global issues explored in our stories and lessons include the following: 気候変動, cultural displacement, corporate abuses, cultural preservation, food insecurity, グローバル化, 人権, 移民, language loss, マイグレーション, modernization, 貧困, and sustainability. Through the stories, students can connect to a world much bigger than the one they know, ask global to local questions, and think of potential solutions.

How can we prepare students to become perceptive and engaging global citizens? One of my favorite films, which gets to the heart of global citizenship, です 地球の出. The film tells the story of the Earthrise photograph, taken in 1968 on the Apollo 8 mission. Told solely by the Apollo 8 astronauts, the film captures the beauty, awe, and grandeur of the Earth against the blackness of space. This was the first time in history that humanity witnessed the Earth as one ecosystem and one shared home.

I particularly enjoy this passage from the director of 地球の出, エマニュエル・ヴォーン=リー. He wrote, “I wanted to create that human connection to the Earth…I wanted to explore how to feel and witness the Earth as our home the way the Apollo 8 astronauts had. I wanted to share the awe and beauty they had experienced, to remember the power of this image they shared with the world.”

Our Project aims to make connections that highlight humanity’s interconnectedness on multiple levels to allow students to develop empathy and care for our world. Getting to the heart of global learning is making global issues relevant and accessible for students to evolve as self-confident global citizens.

“Many teachers are creating PBL projects using our stories as a foundation.” – クリアリーヴォーンリー

A teacher wants to implement the Global Oneness Project program in his/her curriculum. How does she/he get started?

最初の, I would recommend viewing this short video clip, which provides an overview of the Project. その後, to get an overview of the stories we tell, watch this 3-minute film reel.

Our website contains over 50 short documentary films, ranging in length from 3-25 分, オーバー 40 photo essays, which geographically span the globe and represent communities on every continent. All of resources are free; you do need internet access. You might be a social science educator looking for a story from a particular region in the world or an English language arts teacher looking for ways to bring in a specific theme that connects to the curriculum’s reading assignments. School districts have also added our resources into their curriculum maps.

To start, I always recommend choosing a story that inspires the educator. All of our stories highlight elements of culture including family, religion and beliefs, 言語, societal rules, 経済, 文学, and traditions. Most times, in our professional development workshops, educators share their own cultural heritage stories after watching a film. These stories make their way back to the classroom, providing meaningful connections. One story many educators begin with is マリーの辞書.

学生の選択と学生の声が教室のためのあなたのプログラムに組み込まれていますどのくらい?

The stories on our website are curated into various collections, including ones on migration, 気候変動, endangered cultures, nature, inspiring people, と創造. We frequently create additional collections on specific themes, such as ones on youth perspectives, 共感, breaking down stereotypes, family traditions, and identity and place. These collections are used by educators, specific to their subject focus and instructional goals, and provide ways for students to select a story of their choice.

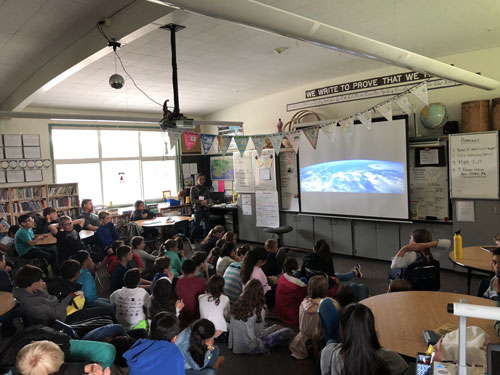

Many teachers are creating PBL projects using our stories as a foundation. Students choose a story, surrounding a particular theme or global issues, conduct research, 質問をする, respond to writing prompts, and present their findings in their classroom or during school-wide events. Projects take the shape of public service announcements, short films, 詩, 写真撮影, and letters to the filmmakers or to community leaders. Our films are also used in classrooms or during school-wide film festivals or screenings. Students then host panel discussions with their communities to think deeper about global issues and offer potential solutions.

“How can students contribute to creating a better world? There is an urgency to address this question.” – クリアリーヴォーンリー

あなたが直面してきた最大の課題は何ですか?

One of the biggest challenges we face is staying up to date with emerging technologies. The technology of virtual reality, 例えば, is not yet accessible to the mainstream. What role will these technologies have on the future of education?

What can we expect from the Global Oneness Project in the next 10 年? あなたの主な目標は何ですか?

We’ll need stories that highlight our common humanity as much as we need them now. How can we challenge students to create more solutions-based thinking towards some of our most pressing global issues? We will ask ourselves this question as we move forward.

We will continue to offer educators and students free tools and resources to explore universal values through immersive storytelling. It is our hope that these stories will inspire teachers to approach learning from a personal perspective and encourage students to make informed decisions, persist through challenges, become effective problem solvers as well as cultural and environmental stewards. How can students contribute to creating a better world? There is an urgency to address this question.

C言語. M. Rubin and Cleary Vaughan-Lee

私たちにありがとう 800 プラス グローバル貢献, 教師, 起業家, 研究者, ビジネスリーダー, 学習の未来とのあなたの視点を共有するためのすべてのドメインからの学生と思想的指導者 教育のためのグローバル検索 毎月.

C言語. M. ルービン (キャシー) CMRubinWorldの創設者であります, オンライン出版社は、世界的な学習や惑星教室の共同創設者の将来に焦点を当てました. 彼女は3ベストセラー本や2つの広く読まオンラインシリーズの著者であります. ルービンは、受信しました 3 「教育のためのグローバル検索」のアプトン・シンクレア賞. に発売されたすべての学習者のために提唱シリーズ 2010 そして国が直面している重要な教育問題を探求するために世界中から著名な思想的指導者を結集.

Cに従ってください. M. Twitterでルビン: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

最近のコメント