“米中が、. パーソナライズされた学習についての増加の会話があります, デジタル学習, より深い学習を問わず, ほとんどの学校で普及しているコンテンツ配信メカニズムは、従来のまま, 20学習への世紀のアプローチ. チュートリアルのネットワークは、私たちの戦略は、学習の過程で学生を従事するものについての会話を開始する機会を与えます。” – ヘレン·ジャン·マローン

子どもを学習の中心に戻すと何が起こるか?

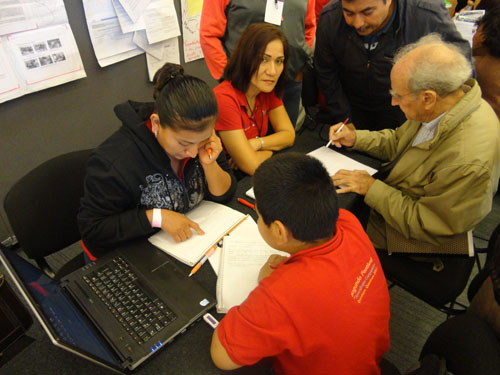

This simple philosophy was used to launch an experiment with the goal of improving eight poor rural Mexican public schools. から 2009, the tutorial networks (as the grassroots initiative was called) have been leading a country-wide school improvement effort in 9000 schools with the lowest academic achievement on the national standard test. パート今日 4 の “教育は私の右か,” 我々は今公立学校の教育のメキシコの中央集権システムの教育者や政策立案者によってサポートされているような肯定的な結果を達成したこのユニークで革新的な戦略から学ぶことができるものを教育改革探る。.

It is my pleasure to welcome to The Global Search For Education, ガブリエルハウス, メキシコシティベースのConvivencia Educativaの創始者 (教育の共存) A.C. メンタリングとネットワーキングS.C. (メンタリングネットワーク). I also asked Helen Janc Malone, author of Leading Educational Change: グローバルな問題, 課題, 全システムの改革に関すると教訓, which features Gabriel’s work, 重量を量るために. ヘレンは、ワシントンでの教育リーダーシップ研究所の機関振興のディレクターである, DC.

Advertisement

“Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, 機会が深く学ぶために、グループ内の陽気なコミュニティを作成することになる。” – ガブリエルハウス

ガブリエル, チュートリアルのネットワークの目標を要約してください.

公立学校でのチュートリアルのネットワークは、教師と生徒が学ぶべきテーマを決定する支配的な文化の学習者に課せられた主要な歪みを解消するための手段である, 彼らが習得する必要があり、その中及び回. 代わりに、有能なメンターと興味を持って学習者の自由な出会いを可能にする, standard practices in classrooms force impersonal recitations of content to generally passive audiences. The known effect is not only lack of interest in the particular subject being presented, but the missed opportunity to practice learning academic subjects in earnest, with commitment, visible results and satisfaction – the foundations of the enduring ability to learn by oneself. Contrary to common practice, 教室でのチュートリアルの関係はメンター·グラフィックスのレパートリーで何ができるのかを各生徒に興味のあるもののマッチングを促進する. 即時の異議, 従来の視点から, 1教師が大きなグループ内のすべての生徒の興味と一致することは不可能によく近付いになるということです, 教師は知識と助けて喜んであっても、. チュートリアルのネットワークは異議を偏向, グループ内のすべてのメンバーがお互いから学ぶように. Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, becomes the occasion to learn in depth and to create a convivial community in the group.

Tutorial networks were first started at the margins of a public school system, where chronic deficiencies in structure, transient teachers, and regional poverty were invitations to try radical innovations, without disturbing the rest of the schools. As regular classrooms turned into learning communities and students became capable of mentoring what they had mastered, opportunities to learn multiplied: students moved eagerly to neighboring schools to share what they knew with fellow students, and in turn, these students and their teachers created new learning communities. その後, authorities changed from allowing a radical experiment in almost lost cases to promoting tutorial networks to improve learning in low performing, though better served schools. This way the transformation began to be seen as a large scale educational change.

二つの主要な要因は、すでにメキシコの公立学校の数千に触れた形質転換のために占める: システムを担当する当局の受け入れ, もちろん, しかし最も印象的, 近隣の学校で自分自身の学習の経営者と変化の活性剤への外部ディレクティブの受動的な受容体から教師と生徒の内側の変換. 普通の教師と生徒の間で新たに発見された電力, だけでなく、学ぶために, だけでなく、教えるために, has proved to be the major force to sustain and spread tutorial networks in the school system.

As the basic competency of taking control of one’s own learning becomes regular practice among a growing number of educational actors, the possibilities of a more professional service increase.

“Once the competency of controlling and sharing one’s own learning becomes the basic link in an extended network of advisors, 教師, students and even their families, the groundwork of an autonomous profession is laid out.” – ガブリエルハウス

What have been the benefits and what have been the challenges?

The major benefit has accrued to teachers and students who perceive, as never before, the satisfaction of achieving visible, valuable learning. The obvious reason is the perfect match of interest and capacity that obtains in tutorial dialogues when tutor and tutee face a common challenge. Basic to the success also is the equity of the exchange predicated on mutual trust, truth and commitment. Such an exchange invariably leads to completion, always satisfactory in a real sense, never deferred to some vague future, and always open to further intellectual achievements. The evidence of good learning and the fruition of excellence come when the tutee becomes a tutor to fellow students, to family members and at times even to neighboring teachers and administrators. Exchanges among students of different schools in order to give and receive tutoring become natural, even necessary to demonstrate competency, increase common knowledge and extend the practice.

Once the competency of controlling and sharing one’s own learning becomes the basic link in an extended network of advisors, 教師, students and even their families, the groundwork of an autonomous profession is laid out. Training, 教え, evaluating, managing school chores and administering resources are easily integrated and make possible the rendering of the quality service expected from a public school system.

The new relationships that started at the learning core create stronger social relationships within the school system, and in a very real sense democratize the institution, since the newly discovered power of every learner commands the process.

チュートリアルネットワークの継続的な拡大への挑戦, いつものように, 彼らが約束した結果を提供しない場合でも、次しようとしたパターンの根深い習慣です. これは、深さに学び、それを共有し楽しむために、内変換の原因となる出会いを対面での良い結果の満足のいく経験です.

“これらのネットワークは数年の方法で、学校の数千に数十から広がっていると信頼性の改善アプローチとして教育機関に受け入れられてきたという事実, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large. -ヘレン·ジャン·マローン

ヘレン, what can we learn from this approach to school reform?

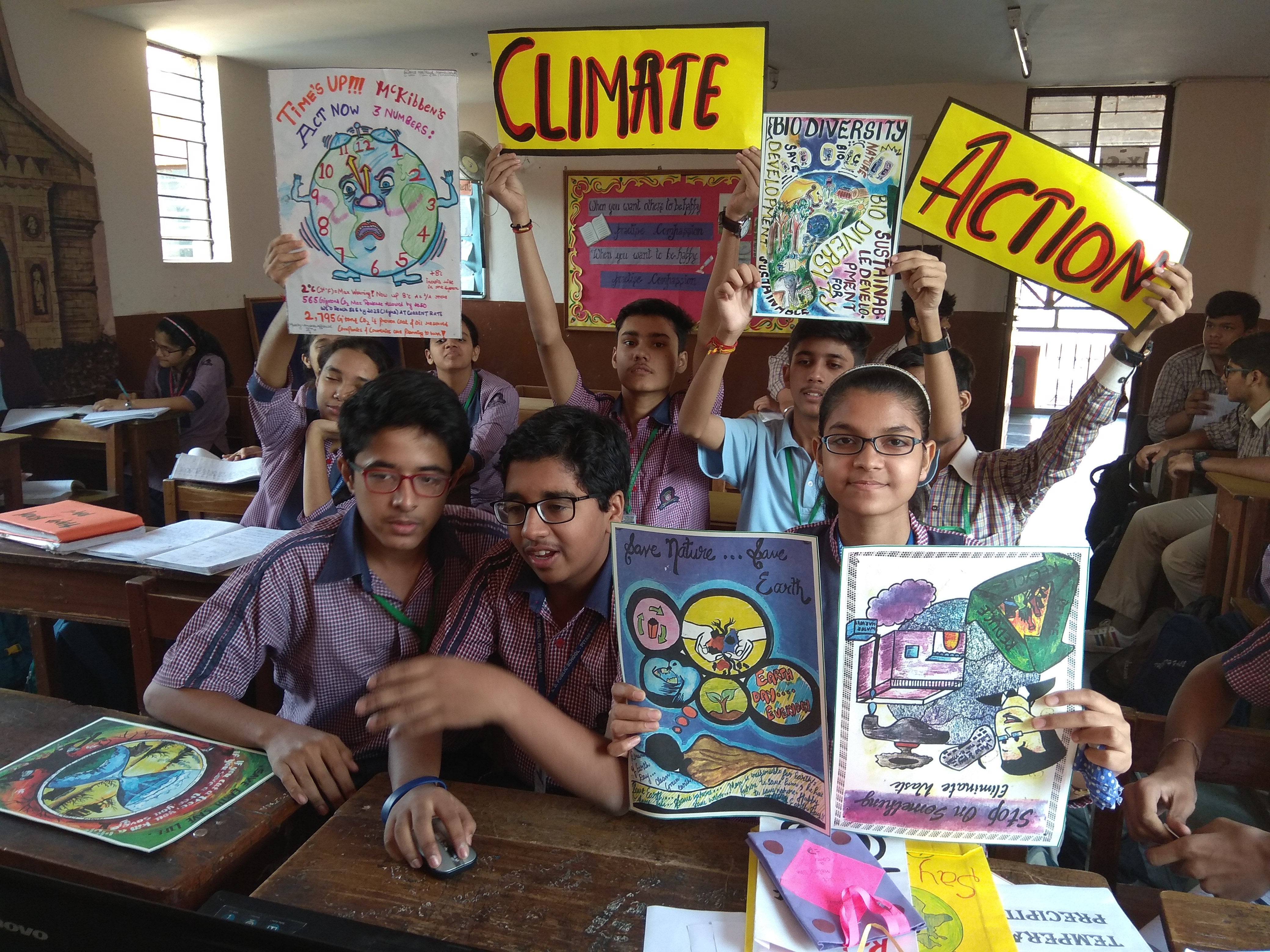

Tutorial networks in Mexico turn school reform on its head. As opposed to hoping educational change trickles down from national or regional policies and external pre-packaged reforms, tutorial networks create change from the grassroots level. これらのネットワークは数年の方法で、学校の数千に数十から広がっていると信頼性の改善アプローチとして教育機関に受け入れられてきたという事実, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large.

What is unique and innovative about the tutorial networks is that they put the learner and the process of learning at the center of the education endeavor, and focus on tutorial relationships as a driver for democratic, equitable learning environment, absent of traditional, grade-level, standardized, rigid structures that often disengage students. Taking agency for instructional delivery and ownership of learning is empowering and motivating for both the tutors and the tutees. There is a great sense of pride that comes from receiving personalized learning, mastering content and sharing that knowledge with peers. An added advantage of such a strategy has been the excitement that spreads beyond the school walls and spills out into the community, where families again begin to see schools as centers for learning and development. チュートリアルのネットワークが積極的に農村変換することができた場合に特に明らかである, 高貧困, 低パフォーマンスの学校.

米中が、. パーソナライズされた学習についての増加の会話があります, デジタル学習, より深い学習を問わず, ほとんどの学校で普及しているコンテンツ配信メカニズムは、従来のまま, 20学習への世紀のアプローチ. チュートリアルのネットワークは、私たちに戦略が学習の過程で学生を従事するかについて会話を開始する機会を与える.

ヘレン·ジャン·マローン, C.M. ルービン, ガブリエルハウス

すべての写真ジェシカTrujanoの礼儀である.

For more information see Leading Educational Change: グローバルな問題, 課題, 全システムの改革に関すると教訓 (ティーチャーズカレッジプレス, 2013): http://store.tcpress.com/0807754730.shtml

教育のためのグローバル検索で, サー·マイケル·バーバー含め私に参加し、世界的に有名なオピニオンリーダー (英国), DR. マイケル·ブロック (米国の), DR. レオンBotstein (米国の), 教授クレイ·クリステンセン (米国の), DR. リンダダーリング·ハモンド (米国の), DR. マダブチャバン (インド), 教授マイケルFullan (カナダ), 教授ハワード·ガードナー (米国の), 教授アンディ·ハーグリーブス (米国の), 教授イヴォンヌヘルマン (オランダ), 教授クリスティンHelstad (ノルウェー), ジャンヘンドリクソン (米国の), 教授ローズHipkins (ニュージーランド), 教授コーネリアHoogland (カナダ), 閣下ジェフ·ジョンソン (カナダ), 夫人. シャンタルカウフマン (ベルギー), DR. エイヤKauppinen (フィンランド), 国務長官タピオKosunen (フィンランド), 教授ドミニクラフォンテーヌ (ベルギー), 教授ヒューローダー (英国), 教授ベン·レビン (カナダ), 主ケンマクドナルド (英国), 教授バリー·98名 (オーストラリア), シヴナダール (インド), 教授R. Natarajan (インド), DR. PAK NG (シンガポール), DR. デニス教皇 (米国), Sridhar Rajagopalan (インド), DR. ダイアンRavitch (米国の), リチャード·ウィルソン·ライリー (米国の), サー·ケン·ロビンソン (英国), 教授パシSahlberg (フィンランド), 教授佐藤学 (日本), アンドレアス·シュライヒャー (PISA, OECD), DR. アンソニー·セルドン (英国), DR. デビッド·シェーファー (米国の), DR. キルスティン没入Areの (ノルウェー), 首相スティーブン·スパーン (米国の), イヴTheze (リセ·フランセ·米国), 教授チャールズUngerleider (カナダ), 教授トニーワーグナー (米国の), デイヴィッド·ワトソン (英国), 教授ディランウィリアム (英国), DR. マークWormald (英国), 教授テオWubbels (オランダ), 教授マイケル·ヤング (英国), 教授Minxuan張 (中国) 彼らは、すべての国が今日直面している大きな絵教育問題を探るように.

教育コミュニティページのためのグローバル検索

C言語. M. ルービンは彼女が受け取った2つの広く読まれているオンラインシリーズの著者である 2011 アプトン·シンクレア賞, “教育のためのグローバル検索” そして “私たちはどのように読み込みます?” 彼女はまた、3冊のベストセラーの著者である, 含めて 不思議の国のアリスリアル.

Cに従ってください. M. Twitterでルビン: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

最近のコメント