The take home for me from Katie Couric’s recent report on Lyme disease is that there are still too many unanswered questions. We need more research to understand Lyme, which affects 300,000 victims each year because we don’t have answers. We do know the term “chronic Lyme” is a conversation stopper in some medical circles, although most doctors seem to agree that when Lyme is caught late in patients, it can lead to their becoming persistently ill with chronic-like symptoms after antibiotic treatment. Are these symptoms due to Lyme, co-infections from the same tick bite, or something else? The evidence that there is something more complex going on seems substantial.

A team of scientists led by Dr. Monica E. Embers of the Tulane National Primate Research Center and Dr. Stephen W. Barthold, Director of the Center of Comparative Medicine at the University of California at Davis, carried out two experiments last year on rhesus macaques (monkeys) to determine whether Borrelia persists after antibiotic treatments. The studies published in PLOS ONE explored antibiotic efficacy using nonhuman primates. Rhesus macaques were infected with B. burgdorferi and a portion received aggressive antibiotic therapy 4-6 months later. The results demonstrated that B. burgdorferi can withstand antibiotic treatment, administered post-dissemination, in a primate host. I was able to speak with Monica Embers about the research and her goals moving forward.

Please briefly explain to me your Borrelia research projects.

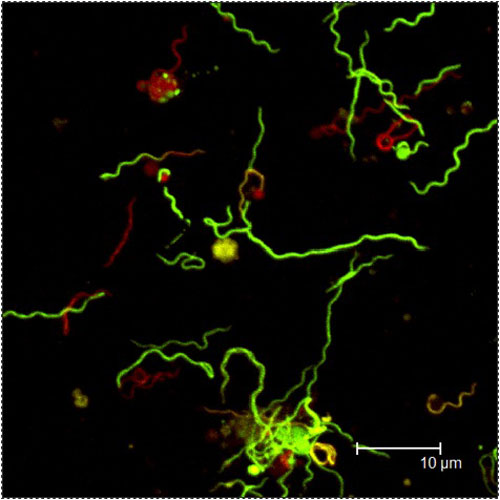

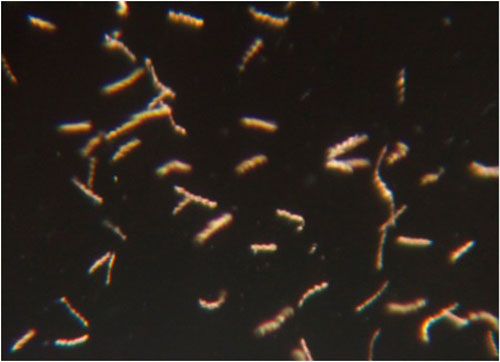

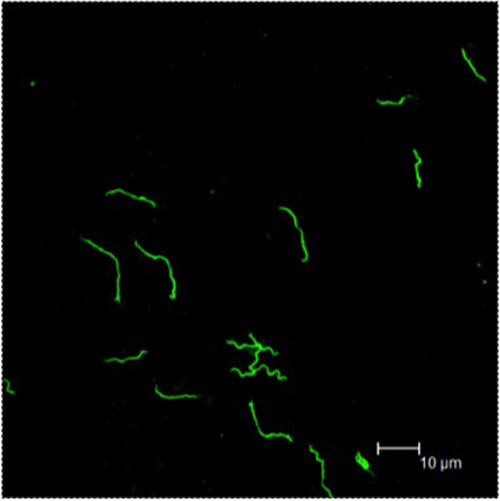

We have several research projects, but the most well known is the one devoted to the assessment of antibiotic efficacy in Lyme disease. While we have shown that intact Borrelia spirochetes can persist following a standard duration of treatment following disseminated infection, we do not know if those spirochetes linger and cause disease or if they are eventually cleared. Além, we do not know if those spirochetes recovered post-treatment are still infectious. We are investigating this both from the perspective of the host and from the bacteria. With regard to the host, we are in the process of inspecting tissues of infected/treated monkeys for evidence of pathology and for the presence of Borrelia spirochetes. With regard to the bacteria, we are examining how doxycycline affects the phenotype (characteristics) of the bacteria and how they may be able to tolerate the antibiotic environment when inside a host.

How would you describe the other research progress you have made to date?

We have performed analyses of the pharmacokinetics for doxycycline in rhesus macaques (basically, determining the blood levels over time after a specific dose) Porque: (1) that information was not available; e (2) to validate our persistence study. We have also repeated the study on persistence using infection by tick, but the results are not yet complete.

Has your finding of the persistence of Borrelia following antibiotic treatment been replicated by anyone? Has it been peer reviewed and published? Se assim – qual foi a reação crítica?

Antes da publicação do nosso trabalho, Borrelia burgdorferi foi detectada após o tratamento com antibióticos em camundongos e cães. Quanto a outros replicando nossos estudos, isso é improvável devido ao custo do uso de macacos. Conforme relatado em nosso artigo PLOS ONE revisado por pares (http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0029914), contudo, nos apresentamos 2 experimentos independentes com diferentes cepas e regimes de tratamento, e foram capazes de encontrar evidências de persistência em ambos. Este trabalho foi objeto de uma crítica publicada (ver http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/vbz.2012.1012) principalmente pela falta de dados farmacocinéticos/farmacodinâmicos nos macacos. Sabíamos que isso era uma fraqueza, mas a informação não estava disponível (do trabalho publicado) quando realizamos os experimentos. Eu obtive o financiamento e comecei esses estudos antes da crítica. este(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jmp.12031/abstract;jsessionid=B670DDD58DC902AD3D38C256953639B0.f01t02) validou nossa dose de doxiciclina (which was much higher than needed) in Experiment 2 of that paper. Another criticism was that we used a high dose of bacteria for the inoculum. We did this to insure that the animals became infected. What impact the initial dose has on treatment months later, I do not know, but we are now in the process of repeating the experiment using tick-mediated infection.

If the Borrelia spirochetes are still infectious, what would be evident in the monkey tissues? What would you expect to see in persistent bacteria if the doxycycline had neutralized them?

One would expect to see signs of inflammation (immune cells and chemical mediators) in the affected tissues. Isso fortaleceria os dados se B. burgdorferi foram realmente detectados nesses tecidos também. Existem certas imunidades (anticorpo) respostas que só podem ser vistas em uma infecção produtiva também. Nosso laboratório está analisando isso. Se as bactérias persistentes não forem infecciosas, eles podem ser prejudicados em sua capacidade de disseminar e ocupar locais no corpo distantes do local de inoculação. Também não se espera que induzam inflamação em tecidos distantes.

Quais doenças você conhece em que as bactérias persistentes após o tratamento com antibióticos não causam doenças?

Há exemplos como a sífilis (também uma espiroqueta) e o patógeno que causa a tuberculose em que a bactéria na ausência de antibióticos vive dentro do hospedeiro por longos períodos de tempo sem causar doença. There are other examples of bacteria that persist post-antibiotics in protective niches called biofilms. Na minha opinião, these do not lead to controversy because they can still be detected and cultured. B. burgdorferi is not known to form biofilms inside the host, nor is it readily detected or cultured following antibiotic treatment. This makes it very difficult to understand the nature of these spirochetes that persist.

What eventually happens to the bacteria that persist in diseases (other than Lyme) where they do not cause disease?

In the case of M. tuberculosis, the bacteria can become encased in granulomas in the lung, where they live in a state of dormancy protected from the immune system of the human host. In the case of syphilis, the spirochetes enter a dormant phase, but where exactly they hide in the body? I’m not sure if it is known.

Regarding B. burgdorferi and biofilms, I am aware of several pieces of research that claim that these bacteria do form biofilms and pods, where they hide from antibiotics. Are you familiar with this research?

I am aware of Eva Sapi’s work. This is very interesting to consider. I chose the wording “B. burgdorferi is not known to form biofilms inside the host,” because the work has been done in vitro and has not been shown in animals. This is not to say that it doesn’t occur, but it just hasn’t been shown to occur inside a mammal.

What are some of the research challenges that you face at present?

For any researcher, the acquisition of funding is a challenge. It is not possible to pursue all of your ideas and interests without the funds to do so. Dito, I still feel fortunate to be able to do the work that I have just described. The monkey model has no guarantees, likely because it is so similar to humans. Por exemplo, some monkeys may self-cure, some may get a rash or arthritis, and each may have a different immune response to infection. Unlike mice, it is also very unlikely that the spirochetes can be cultured from tissues of an infected animal, whether it is treated or not. Some consider culture a “gold standard” for viability of the bacteria and it is simply not possible. Like humans, they are out bred and exhibit tremendous variability in disease manifestation.

If not cultures, what do you believe are the best methods for demonstrating the existence of bacteria in the blood?

Bem, Borrelia is only found in the blood during early infection. If we can’t culture them, then xenodiagnosis is probably the best alternative. To test if they are viable, recovered spirochetes (from ticks) would need to be injected into a naïve animal.

Why do you believe your research should be a priority?

There are very specific ways in which the nonhuman primate model of Lyme disease is valuable. The monkey may be considered an incidental host, like humans, whereas the mouse is a reservoir host for Borrelia in nature. This means that the spirochetes have evolved to cause little disease (with the exception of some laboratory strains) and grow readily inside mice. Mice do not get a rash or infection of the brain and their immune response to infection is not the same as the human immune response. For studying the host response to infection, an animal model closer to humans can therefore provide a significant advantage. Studying Lyme disease in humans is limited to available body fluids for analysis and the infection history may be unclear. Em resumo, there are many variables that cannot be controlled in studying human patients. Monkeys provide a model similar to humans in which we can control variables such as infection history and monitor disease progress, to include the examination of tissues post-mortem. This model can be used to evaluate diagnostic tests, com o benefício de saber exatamente quando e com o que o animal foi infectado. Pode ser usado para determinar se a verdadeira patologia persiste após o tratamento com antibióticos, e foi disponibilizada uma nova vacina, apresentaria um modelo ideal para testar a segurança e eficácia da vacina.

Quais são os próximos passos no processo de pesquisa de Lyme?

Da maneira que eu vejo, o próximo passo é determinar se as espiroquetas que persistem após o tratamento com antibióticos são infecciosas. Já sabemos dos estudos com ratos do Dr.. Stephen Barthold que eles não são cultiváveis, mas isso significa que eles são “morta?” Ele mostrou que espiroquetas de um camundongo tratado com antibióticos que foram transplantados ou transferidos para camundongos imunodeficientes podem ser detectados (por seu DNA) em vários tecidos, significando que eles (ou pelo menos seu DNA) havia disseminado. We need to find a way to test the viability of these spirochetes and establish whether or not they can cause disease. Essentially, we need to physically acquire and isolate the spirochetes from an infected/treated animal and transfer them to another animal to show that they do or do not cause disease. This is the basis of Koch’s postulates.

Para mais informações sobre o Dr.. Monica Embers:

http://www.tnprc.tulane.edu/division_bacteriology.html

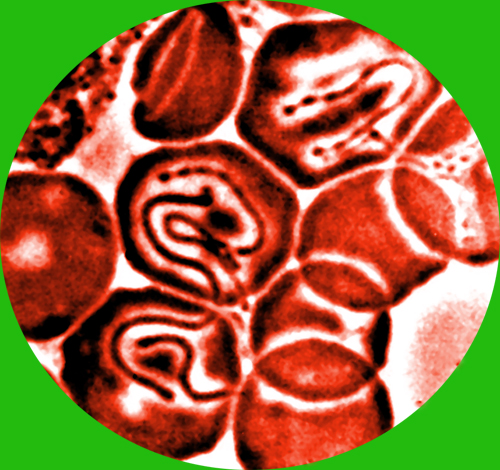

All photos are courtesy of Monica Embers.

Para mais artigos Carrapatos: clique aqui

Na busca Global para a Educação, se juntar a mim e líderes de renome mundial, incluindo Sir Michael Barber (Reino Unido), Dr. Michael Bloco (EUA), Dr. Leon Botstein (EUA), Professor Clay Christensen (EUA), Dr. Linda, Darling-Hammond (EUA), Dr. Madhav Chavan (Índia), Professor Michael Fullan (Canadá), Professor Howard Gardner (EUA), Professor Andy Hargreaves (EUA), Professor Yvonne Hellman (Holanda), Professor Kristin Helstad (Noruega), Jean Hendrickson (EUA), Professor Rose Hipkins (Nova Zelândia), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canadá), Honrosa Jeff Johnson (Canadá), Senhora. Chantal Kaufmann (Bélgica), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finlândia), Secretário de Estado Tapio Kosunen (Finlândia), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Bélgica), Professor Hugh Lauder (Reino Unido), Professor Ben Levin (Canadá), Senhor Ken Macdonald (Reino Unido), Professor Barry McGaw (Austrália), Shiv Nadar (Índia), Professor R. Natarajan (Índia), Dr. PAK NG (Cingapura), Dr. Denise Papa (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Índia), Dr. Diane Ravitch (EUA), Richard Wilson Riley (EUA), Sir Ken Robinson (Reino Unido), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlândia), Professor Manabu Sato (Japão), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCDE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Reino Unido), Dr. David Shaffer (EUA), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Noruega), Chanceler Stephen Spahn (EUA), Yves Theze (Lycée Français EUA), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canadá), Professor Tony Wagner (EUA), Sir David Watson (Reino Unido), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Reino Unido), Dr. Mark Wormald (Reino Unido), Professor Theo Wubbels (Holanda), Professor Michael Young (Reino Unido), e Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) como eles exploram as grandes questões da educação imagem que todas as nações enfrentam hoje. A Pesquisa Global para Educação Comunitária Página

C. M. Rubin é o autor de duas séries on-line lido pelo qual ela recebeu uma 2011 Upton Sinclair prêmio, “A Pesquisa Global para a Educação” e “Como vamos Leia?” Ela também é autora de três livros mais vendidos, Incluindo The Real Alice no País das Maravilhas.

Comentários Recentes