The desire for successful children in a performance-based culture often consumes us before we realize it. “多いほど良い” 無邪気に考え方に滴り落ちるかもしれません, しかし、あなたがそれを知る前に, 勝者は競争社会のすべてのダイナミクスを取り、簡単に私たちの日常生活の一部になることができます. Whether it’s coming from inside or outside of school, the need for our children to succeed is coming at us fast and consistently.

I recently found myself pondering what style of parenting ultimately creates the best foundation for our children. Amy Chua (Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother) on the one hand proposed that the best way for a parent to prepare kids for a successful future is to stress academic performance, never accept a mediocre grade, and instill a deep respect for authority. ヴィッキ·アベルズ (どこにもへレース) was concerned that performance pressure on kids is destroying self-esteem and happiness, and stifling creativity.

Should self-esteem and happiness come before accomplishment, or accomplishment before self-esteem? Perhaps success might be a delicate balance between the two that we each must define for ourselves and then evaluate on a regular basis?

This is the first of three in depth looks at student health and engagement with learning. This week I have the pleasure of sharing the perspectives of Dr. デニス教皇, 教育のスタンフォード大学医学部. Pope specializes in student engagement, curriculum studies, qualitative research methods, and service learning. She founded and served as director of Stressed-Out Students (SOS), the predecessor to Challenge Success. 彼女の本, Doing School: How We Are Creating a Generation of Stressed Out, Materialistic, and Miseducated Students, was awarded Notable Book in Education by the American School Board Journal.

Are you seeing an increase in the number of cases related to adolescent anxiety, stress or depression?

The answer is yes. We are seeing more cases in terms of higher stress levels and in terms of anxiety, うつ病, and other diagnosed disorders than we have seen in the past. A study done by Stanford Medical Center a few years ago confirmed this (DR. Jun Ma, 2005, Journal of Adolescent Health). You might say we are getting better at detecting mental health issues in kids, so you might wonder if that is the cause of the increase that we see. The experts believe that there is definitely something going on around this notion of kids being much more stressed these days – above and beyond the better detection rates.

Can we connect it to academic pressure?

Our Challenge Success survey (26 学校, 10,275 学生, 87% high schools, と 65% of them public) gave the kids a worry and stress scale. 67% of our sample said they are often or always stressed about school. On the qualitative question, i.e. “what if anything causes you stress,” the top ten answers from the majority of our students were school related. Ten or twenty years ago the top answer for a teen might have been family issues, divorce, bullying or sexual identity, but they would not primarily have been school related. Granted we were talking to high achieving schools and we were doing the survey in school, but even given that, the top answers were homework, テスト, grades and competition to get into colleges.

Are we able to tell who the vulnerable child is?

The CDC uses GPA as one measure to predict student well-being. What we know at Stanford and other high achieving institutions is that you can have straight A’s and still be in distress. The typical or traditional ways of assessing mental or physical health issues for us are not as accurate anymore. Many of the suicide attempts or suicides that we are seeing at high achieving schools involve kids with good grades. To the outside world, these kids look like everything is okay. 多くの場合, there may be signs that people missed. We have to get better at identifying these signs. The fact that the kid throws himself across the track the first day of AP week might suggest there is a link between academic stress and mental distress. But there are always multiple factors at play when a young person suicides. It can be very hard to tease out what part genetics, うつ病, 環境, and impulsivity play. うつ病, which tends to run in families, is strongly linked to suicide, yet there are many people who never manifest depression and who never suicide in spite of having a strong family history of depression. What we do know is that high levels of stress increase the likelihood of depression manifesting itself. この点において, we have an obligation to keep the level of stress in our children’s lives manageable. High levels of stress can cause distress and make our children vulnerable to a host of physical, cognitive and emotional problems.

Who or where is the stress coming from?

Most kids agree it is coming from all areas including parents, self-imposed pressure, and the schools. If you go further, the kids add college, college admissions, and the media frenzy over status, money and success. We call it a systemic cultural issue around a flawed and miscommunicated definition of success. One of the questions we ask the students in our survey is “How do you define success?” From my experience of asking parents the same question, the response I get is “幸福, 健康, giving back to society” – all the things you would expect a parent to say. The first response we get from the kids is “お金, グレード, test scores.” And so we are talking about external definitions versus internal. How are these messages getting so distorted when parents and kids are living in the same house?

Kids in the same family can be very different in terms of their personalities and consequently their outlook, despite being exposed to the same influences. 感想?

There are some kids that parents need to hold back. 例えば, the perfectionist child. You have to say, “This is too much.” You have to play the parent card and say, “It is bedtime or you are not taking that extra class.” And then there are other kids that might need a little kick in the pants – a little more attention and urging them to think about schoolwork and completing homework, because it’s a good thing now and then for a kid who isn’t spending much time on school. But you have to be careful. We know that parents can cause a lot of duress. We also do workshops for parents on values where we look at the question: Are your actions aligning with your values? 例えば, are you saying one thing while at the same time pushing your kids to take extra classes they don’t want, or hiring lots of tutors.

What can be done to better address children and adolescents compromising emotional and physical health as they deal with performance pressure?

This is what we focus on at “Challenge Success.” I believe there should be a process to dealing with performance pressure. I believe there should be intervention. We also don’t believe there is a one size fits all solution. It depends on the level you are working with and the institution you are working with. There also has to be a multi-stake holder team approach. So we work with schools, parents and students to develop a plan of action specific to their school around the issues of student health, 幸福, and engagement with learning. We give school teams a coach who works with them on a consulting basis for a year. We say that every kid needs PDF (プレイタイム, downtime, family time) every day, no matter what the age. We talk about the research we’ve done and how you can protect PDF at any age. 親のため, we do six week education courses (live and online). We ask them to think about their value system and come up with their own definition of success and an action plan of how they’re going to apply this vision to their parenting practices. We have seen schools do a lot of different things that has definitely dialed down the stress level and improved the health and well-being of the kids. We use hands-on solutions to what is a very large cultural problem, and schools keep coming back. We are definitely making a dent. If you don’t have healthy kids, they are not going to be successful, 期間!

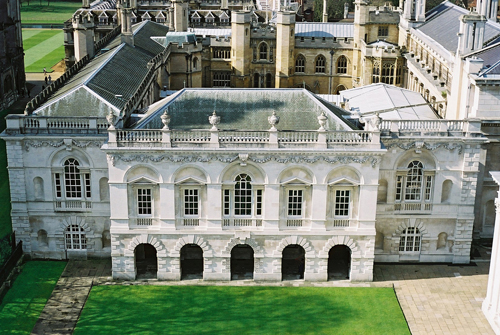

Photos courtesy of Stanford University School of Education.

中に 教育のためのグローバル検索, サー·マイケル·バーバー含め私に参加し、世界的に有名なオピニオンリーダー (英国), DR. レオンBotstein (米国), DR. リンダダーリング·ハモンド (米国), DR. マダブチャバン (インド), 教授マイケルFullan (カナダ), 教授ハワード·ガードナー (米国), 教授イヴォンヌヘルマン (オランダ), 教授クリスティンHelstad (ノルウェー), 教授ローズHipkins (ニュージーランド), 教授コーネリアHoogland (カナダ), 夫人. シャンタルカウフマン (ベルギー), 教授ドミニクラフォンテーヌ (ベルギー), 教授ヒューローダー (英国), 教授ベン·レビン (カナダ), 教授バリー·98名 (オーストラリア), 教授R. Natarajan (インド), DR. デニス教皇 (米国), Sridhar Rajagopalan (インド), DR. ダイアンRavitch (米国), サー·ケン·ロビンソン (英国), 教授パシSahlberg (フィンランド), アンドレアス·シュライヒャー (PISA, OECD), DR. アンソニー·セルドン, DR. デビッド·シェーファー (米国), DR. キルスティン没入Areの (ノルウェー), 首相スティーブン·スパーン (米国), イヴTheze (リセ·フランセ·米国), 教授チャールズUngerleider (カナダ), 教授トニーワーグナー (米国), 教授ディランウィリアム (英国), 教授テオWubbels (オランダ), 教授マイケル·ヤング (英国), 教授Minxuan張 (中国) 彼らは、すべての国が今日直面している大きな絵教育問題を探るように. 教育コミュニティページのためのグローバル検索

C言語. M. ルービンは彼女が受け取った2つの広く読まれているオンラインシリーズの著者である 2011 アプトン·シンクレア賞, 「教育のためのグローバル検索」と「どのように私たちは読みます?"彼女はまた、3つのベストセラーの本の著者である, 含めて 不思議の国のアリスリアル.

最近のコメント